Kid's Online Halloween Series: Mascot Horror

What is 'mascot horror'? How has it developed alongside other platforms and what are the risks?

Summary:

Mascot horror is a type of video game which relies on the player being attacked by childish-yet-frightening monster characters to create a sense of fear

The sale and promotion of these games has to come to depend on their huge child audiences and merchandise markets

Mascot horror is hard to avoid since the mascots are regularly mixed into child content such as Roblox games and YouTube videos

While not excessively violent, these games carry risks of exposing young children to very frightening content, in particular through the unofficial re-use of the mascots in artwork, memes and other accessible forms of media

In the run up to Halloween we will be publishing a series of articles covering risks and threats to children and teenagers from online horror and its associated games, franchises, media content and platforms. Online horror is obviously a vague term, but we simply mean content related to fear, dread, jumpscares, violent and unsettling imagery - in particular when it is drawn from the world of adult horror content. Film/game worlds and their characters are very popular online (eg Scream, Five Nights at Freddy’s, Pennywise, Huggy Wuggy and Leatherface). They have also found additional audiences since being combined with new forms of media like generative-AI or the Roblox platform.

To cover the risks and what solutions are available to parents, we will present outlines and information drawn from our own research, covering topics like mascot horror, shock content and online games. We hope that these guides will provide useful information that can help you talk to your children and empower families to protect themselves over Halloween and beyond.

What is ‘mascot horror’?

We’ve chosen to cover this topic first because we believe that the mascot horror genre is likely to be a child’s first introduction to online horror content, and we will cover why that is the case below.

Mascot horror is the catch-all name given to a subgenre of horror games (and some films) which generally contain the following themes:

A survival horror set in abandoned or liminal spaces (old toy factory, disused nursery etc)

A typically solo protagonist, who must enter or remain in this space to complete challenges, locate information/objects, uncover a mystery

The main antagonists or villains are warped, childish creatures such as giant toys, animatronic bears, old theme park mascot characters or circus monsters

The key fear-factor is the switch between the mascot’s ‘good’ persona, where they present as innocent and safe, and the mascot’s ‘aggressive’ persona, where their features become distorted and frightening and they chase or stalk the player until they catch them and the game is over.

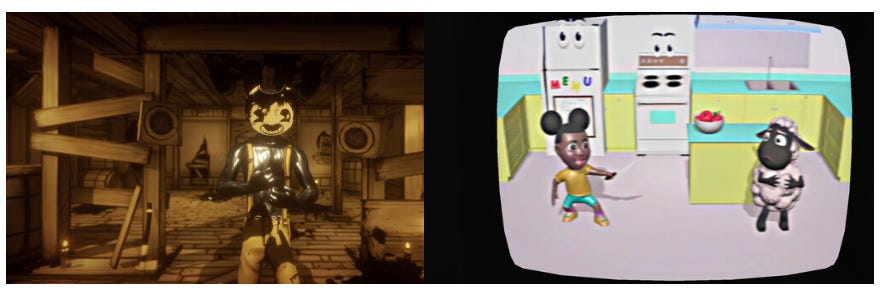

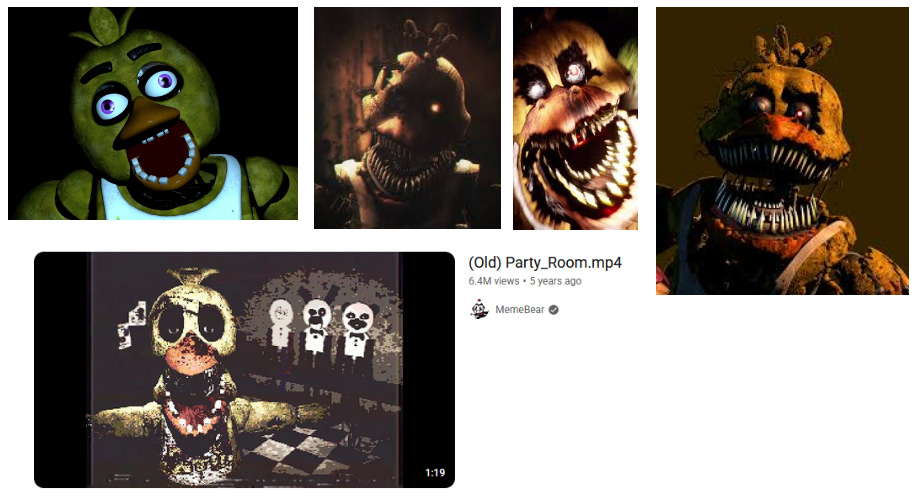

The image below shows some examples of well-known mascot horror characters, and how their appearance changes when the player is attacked with a jump scare.

Alongside the visual effect of a monstrous children’s mascot, these types of horror games are built to create a claustrophobic atmosphere of dread. The player is often defenceless, save for items like cameras, and must rely on closing doors, activating lights and moving quietly to avoid being found. Having to pay close attention to sounds and often playing in low light or sometimes almost pitch black conditions heightens the feeling of fear. When players are spotted by mascots they can be chased, or often just sneak up on them and perform a ‘jump scare’ moment before the game ends.

Other common elements in mascot horror include: themes of kidnapping, missing children, uncanny nostalgia, disturbing back stories and the need to uncover secrets about the mascots themselves. Sometimes the mascots are actually children in some twisted way.

There are many examples of mascot horror games, but the first majorly recognised franchise was Five Nights at Freddy’s, which came out in 2014. Since then hundreds of games have attempted to copy the formula, some finding huge success such as Bendy and the Ink Machine (2017), Baldi’s Basic in Education and Learning (2018), Dark Deception (2018), Poppy Playtime (2021), Rainbow Friends (2022), Amanda the Adventurer (2023) and Garten of Banban (2023). These are often not stand-alone titles, but are released as chapters and follow-up games, continuing the story line. Poppy Playtime has seen four installments so far, with a fifth chapter due for release in January 2026.

Are these games designed for children?

It is very hard to say definitively for an entire genre of games stretching back over a decade whether they are designed for children, and for what age. There is no consistent rating body, since games are released across multiple stores and platforms across different countries. For example, Garten of Banban is often rated anywhere between a ‘general’ and around 9-10+, while Dark Deception has been rated a 7 by Nintendo and a 17+ for the PC version.

In some ways this is irrelevant, since the obvious and immediate attraction of these games to children is baked in from the start. The use of bright, child-friendly mascots which can be portrayed as perfectly innocent naturally draws in kids who see these monsters. It is also irrelevant because the games are designed to be marketed through children, but we’ll come to that.

As far as gameplay is concerned, some mascot horror games are extremely simple, making them accessible to younger audiences. There is typically less blood and gore in these games than other subtypes of horror games, the main ‘fear’ elements coming from the mascots and the atmosphere. Therefore it is hard to say that the entire genre has been made explicitly for kids, but it is also hard to deny their appeal and attraction.

Why are these games so popular?

For adults these games rely on the twisting and subverting of childhood, a trope with immense appeal across all modern media. The locations are associated with childhood, as are the mascots. The artwork can evoke nostalgia or a throwback to older game and video styles - Bendy and the Ink Machine is designed to feel like a 1930’s Disney cartoon, while VHS tapes appear as objects and images across a number of games like Amanda the Adventurer.

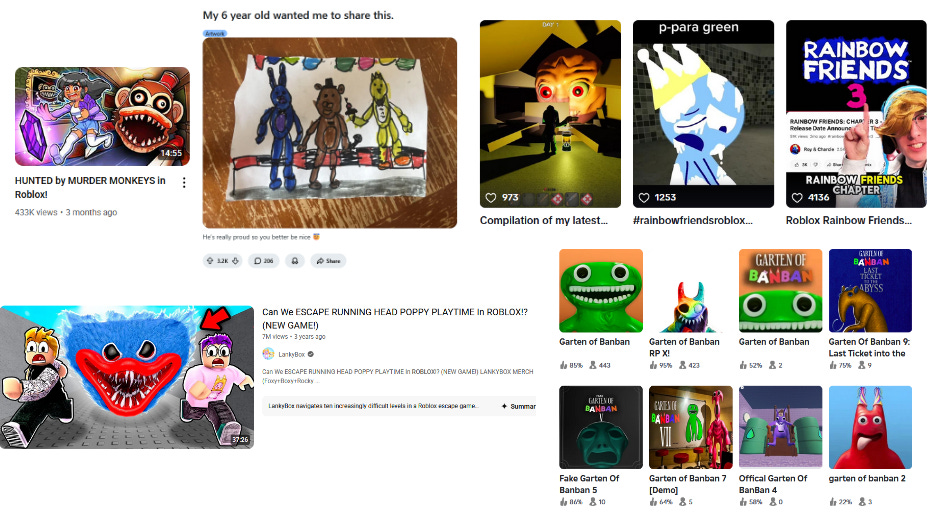

For children, nostalgia is less of an appeal, and the attraction comes from the accessibility and immediate impact of the mascots themselves. Many children know Rainbow Friends and Five Nights at Freddy’s, but they may never have played them.

The crucial factor that has made mascot horror so popular and widespread is that it is largely marketed through social media and streaming platforms. The ease with which Five Nights at Freddy’s was turned from a game into a shared experience through older gamers filming themselves play the game and uploading it to YouTube or filming it live through Twitch. Their scared reactions and physical jumps hooked audiences, many of whom were too young to play the games. Mascot horror was spread through this ‘Let’s Play’ style of video content, and later ‘React’ channels, matching the audience’s desire to see players scream as a nightmarishly cartoon face leered out of the screen. Probably the single most important factor is how perfectly suited horror mascots are for content thumbnails, the form of imagery which drives all modern online media.

This success fed back into game development, and many games seem to have been developed with the explicit intention of being streamed and filmed for gamer channels, sometimes quite cynically in some cases. Beyond YouTube came success in the form of merchandise, toys, branded clothing and stuffy animals. Then came film adaptations. Alongside this, some game franchises allowed themselves to be converted into open, communal fandoms, where copyright was not enforced and players could develop their own modifications, spin-off games and character lore.

Today children are more likely to encounter mascot horror in the form of cross-platform ‘mash-up’ content than through actually playing the original games. Endless versions of mascot characters are churned up with other mascots, worlds, scenarios, until they bear little resemblance to their own franchise context.

This ability to mix-n-match elements of mascot horror with different formats for different audiences is what keeps it continually alive and attractive, and the cycle of game updates and chapter releases maintains the dynamic. It also dissolves the boundary between strictly adult or mature rated content and children, since mascot motifs and characters can simply be transposed from their games into whatever form of content the creator wants.

What are the risks and dangers of mascot horror?

The main risk with mascot horror is the exposure of children to age inappropriate content, and since mascot horror is inherently more appealing and fluid than other forms of horror content, its easy to see how young children might accidentally stumble across it.

There are two main routes:

Exposure to official, within-game content

Exposure to unofficial, user-generated or AI-generated content

There is no doubt that many of these games are inappropriate for children. Within the whole genre some are less viscerally disturbing than others, and parents have to decide for themselves what they feel is appropriate for their child. Alongside the obvious jump scare, atmospheric fear quality of the gameplay, the lore and backstories to these games can hide very mature content from young players. For example, the mascot animatronics in Five Nights at Freddy’s actually contain the bodies and souls of murdered children, a secret the players discover as they move through the game. Similarly in Poppy Playtime the mascots are revealed to be the results of child and animal experimentation.

So, the main risks to children through official game content include:

The specific shock, alarm and distress of seeing a frightening and distorted mascot face. The mascots are intentionally designed to violate a child’s expectations about friendly faces, provoking terror and the ‘uncanny valley’ effect, which develops early in human infancy (Matsuda et al 2012, Tyson et al 2023, Yip et al 2019)

Both younger children and young teenagers who watch horror content may display signs of alarm and distress after the game/film has finished. They may have trouble forgetting what they have seen, leading to anxiety, sleeplessness, shaking, emotional sensitivity and even depression (Martin 2019, Esa et al 2023, Khan et al 2020, Hoekstra, Harris & Helmick 1999, Pearce & Field 2016)

The jump scare moment, combined with the mascot catching them, triggers a sudden adrenaline and fear signal which may be overwhelming for young and novice players/viewers

Unofficial use of the mascot characters and their worlds can produce more extreme and more friendly varieties of content. At the extreme end there is an abundance of user-generated images, stories, games and videos which depict the mascot characters as considerably more frightening than the official developers intended.

There is also a huge market for these mascots being depicted in sexually suggestive or outright pornographic ways, but that leads into a much larger topic about the online use of children’s characters in adult scenarios, to be dealt with in another article.

Obviously the images depicted above are far more aggressive, frightening and upsetting than the official jumpscare image. Therefore the risk of a young child being more frightened, more likely to replay the image in their mind, is much greater.

What can you do?

Parents know their children best and must decide what content they experience and enjoy. Each child is different, and what affects one may not affect another.

Always talk to your child: do they already know these games and characters? How do they feel about them? Have they ever seen anything which made them frightened?

Establish parental safety controls on platforms which may allow these games or spin-off games to be played.

Outside of the official games, platforms like Roblox, YouTube and TikTok regularly produce user-generated mascot horror content, if you are not comfortable with this then use parental control features and discuss with your child what the risks are.

If your child has seen something that upsets them, then they need lots of reassurance and to feel safe. Depending on their age they may need help understanding that the scary mascots are not real, or they may struggle for a while to stop the images recurring in their minds or dreams. Resources for different age groups are available online: younger children, school age, teenagers

Frustratingly many of the academic and popular works dealing with children and horror have not kept pace with the speed of change online. We know very little about how constant exposure to hyper-stimulating content affects childhood and development - parents should trust their own instincts and their relationships with their children to make the right choice, and hopefully resources like this article will help to do that.

References cited

Esa, I.L., Khoirunnisa, S.R., Mona, N. and Zaferina, S.F.N., 2023, October. The effect of watching horror film on health children and adolescents in Indonesia. In The 6th International Conference on Vocational Education Applied Science and Technology (ICVEAST 2023) (pp. 521-532). Atlantis Press.

Hoekstra, S.J., Harris, R.J. and Helmick, A.L., 1999. Autobiographical memories about the experience of seeing frightening movies in childhood. Media Psychology, 1(2), pp.117-140.

Khan, H.Z., Maan, H., Rizvi, W.R., Ghaffar, M., Khan, H. and Zahra, S.M., 2020. Impact of horror movie viewership on the real-life personal experiences of viewers. Ilkogretim Online-Elementary Education Online, 19(3), pp.2658-2673.

Martin, G.N., 2019. (Why) do you like scary movies? A review of the empirical research on psychological responses to horror films. Frontiers in psychology, 10, p.2298.

Matsuda, Y.T., Okamoto, Y., Ida, M., Okanoya, K. and Myowa-Yamakoshi, M., 2012. Infants prefer the faces of strangers or mothers to morphed faces: an uncanny valley between social novelty and familiarity. Biology letters, 8(5), pp.725-728.

Pearce, L.J. and Field, A.P., 2016. The impact of “scary” TV and film on children’s internalizing emotions: A meta-analysis. Human Communication Research, 42(1), pp.98-121.

Tyson, P.J., Davies, S.K., Scorey, S. and Greville, W.J., 2023. Fear of clowns: An investigation into the aetiology of coulrophobia. Frontiers in psychology, 14, p.1109466.

Yip, J.C., Sobel, K., Gao, X., Hishikawa, A.M., Lim, A., Meng, L., Ofiana, R.F., Park, J. and Hiniker, A., 2019, May. Laughing is scary, but farting is cute: A conceptual model of children’s perspectives of creepy technologies. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1-15).